Ida Mae Minnich

Mae was one of the finest people I ever knew.”

Katie Keyes, Perris Historian

BY CONNOR FORBES

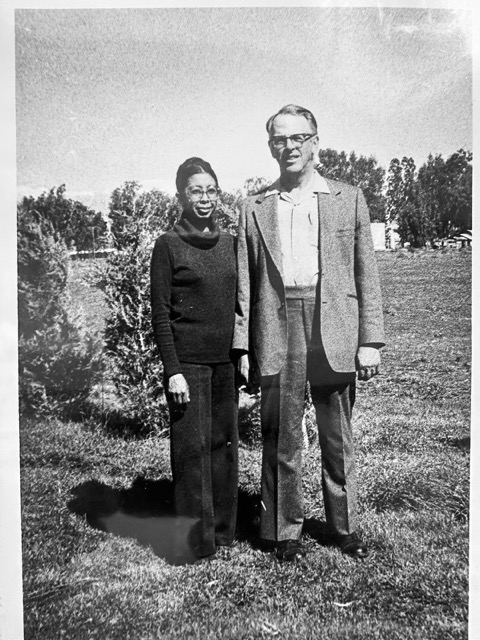

Ida “Mae” Minnich was a big deal in Perris’ history. She, who with her husband, Dwight Benton “Ben” Minnich, owned The Perris Progress in the 1960s, 70s, into the early ’80s was a part of landmark air pollution regulation and volunteered tirelessly for local organizations.

Mae was also the glue that held her family and community together.

She passed away on April 27th, 2024, at the age of 86 from complications from hip replacement surgery.

Mae was born in Colorado in 1937 the eldest child to Teddy and Lena Notarte. At a young age, the family moved to Layton, Utah. Her father passed away in 1954, leaving her to take on a parental role as a teenager to her 2 younger sisters and younger brother, Chi.

Chi (pronounced Ch-eye) Notarte, has fond memories of his sister growing up. Not only was she a wonderful sister, but she was also a mother figure to him being 13 years his senior.

Mae moved to Southern California when she was 18 and started working at Litton Industries in Los Angeles. There she met her husband, Ben Minnich. They married in 1960 and had 2 children, Harvey and Roland. Ben passed away in 2005, son Harvey in 2018.

The young couple moved to Perris the year they married because Ben was heavily involved with the Orange Empire Trolley Museum, now known as the Southern California Railway Museum. Ben, one of the museum’s earliest members, was known nationally for likely being the person most instrumental in preserving more street railway vehicles than any other individual.

The couple bought The Perris Progress shortly after.

“Pappy” Ben Minnich had some experience in the communications field. A graduate of Harvard College, he created a program on the school radio station that only reached the dorms in 1948 called “Barn Howl.” It evolved into “Hillbilly at Harvard” which still airs on WHRB (Harvard Radio Broadcasting) 95.3FM, every Saturday morning.

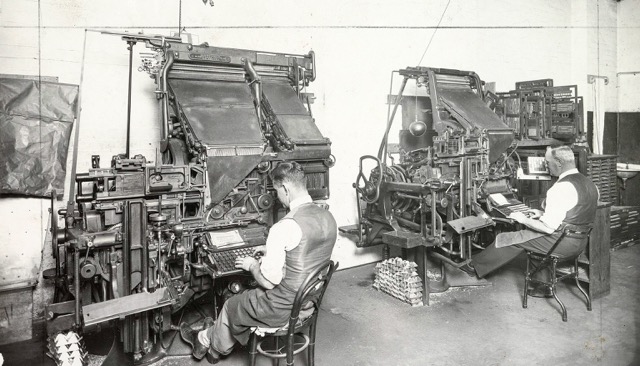

Mae was an integral part of The Progress. In the day, newspapers were composed on large “linotype” machines. Linotype operators typed copy on a keyboard, triggering the melting of metal into the formation of letters, words, and sentences that would go into print. It was slow, arduous, and laborious work, that left no room for error. “Auto-correct” and “cut and paste” were not yet “things.”

Chi remembers Mae set type as fast as anyone in the business, recalling his sister needed to slow down to allow the linotype machine to catch up with her.

She was also proficient in shorthand, practicing on her leg to “record” what was said at family meals to hone her skills. Chi recalls seeing her notebooks full of shorthand and thinking they looked like chicken pecks to him.

The Progress, founded in 1901, became a family affair in the two decades of Mae and Ben’s publishing, generating national subscriptions, drawn to Ben’s “Now That You Mention It” column.

Mae’s youngest son, Roland, recalls late nights, with all family hands on board, finishing the paper together. The proofs needed to be ready for the printer by 4 am. Once, the paper was printed, the Minnich’s would retrieve them from the printer, and set off on the delivery. (editor’s note: This schedule hasn’t changed much with current ownership in the digital age.)

Roland played an important part in the family paper as well. He’d read aloud the public notices to proof them before printing, earning 10 cents per public notice.

In 1970, Ben and Mae bought a property to combine the family home and The Perris Progress office into one location. Today it stands as a mobile home park. Dubbed the No Star Trailer Park by Ben, Roland quipped that the Michelin Guide must not have even known they existed. Located at 150-170 Mapes Rd., it was an especially exciting piece of property to Ben because the northern border abutted the Railway Museum. Mae would continue to run the park with Roland until her passing.

While Mae was instrumental in the operation of The Perris Progress, it was not her full-time job. She worked as an executive assistant to internationally renowned scientist Dr. James Pitts. Dr. Pitts’ work led to air pollution regulation in California (and adopted across the nation and world) that is responsible for cleaner air and car emissions. That regulation resulted in a significant reduction in smog alerts and an increase in visibility across the state. Whenever Roland glances at the mountains, he thanks his mom for her contributions to pulling back the smog and making Southern California’s beauty accessible to all.

During the Minnich’s free time, they loved to travel and go “dinking” (aka road tripping), recalls both Chi and Roland. The term “dinking” was coined by Ben and his love for dinking around on those road trips.

The family piled into their VW Bug and drove as far as they were able. And they were able to go far. Their family drives took them from Baja California to Alaska, and all places in between.

On their dinks, Ben loved to scout for old trolley cars in various states of disrepair. He called it chicken cooping, since at the time trolley cars frequently were converted into chicken coops. Mae was less fascinated with the trolley cars but loved to take in the plant life, the flowers, and the surroundings on these adventures.

After retiring in the 1990s, Mae threw herself into volunteering. She was a part of the Friends of the Perris Library, Perris Valley Women’s Club, Southern California Railway Museum, and Perris Valley Historical Museum.

In 1994 Mae wrote the application for The Perris Depot to be entered onto the National Register of Historic Places. Her volunteering only slowed down with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

May loved to travel until the end. Though she stopped driving a few years back, she still loved road trips. Beginning with his teen years, Chi continued to road trip with Mae a couple of times every year, for the next 60 years. More recently they visited Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks.

Mae will be most missed for her presence, Roland says. He feels fortunate to have spent considerable time with her these last few years. He’ll treasure their walks, road trips with the family dogs, and her proclivity for pointing out flowering plants.

For Chi, Mae was a powerful matriarch of the family keeping it glued together. He finds peace in knowing his sister lived a complete life, doing everything she wanted to do and saying everything she wanted to say.

“Mae was one of the finest people I ever knew,” says Katie Keyes, director of the Perris Valley Historical Museum.

For More Perris News Visit www.zapinin.com/perris.