Seizing a Moment to be Thankful

By Don Ray

As Thanksgiving approached, I spent the last couple of weeks on the streets of Riverside County getting to know some of the unfortunate folks we used to refer to as “homeless,” but now identify as “unhoused.” I was curious to know what, if anything, might make them feel thankful.

As a result, if I were in charge, I’d require everyone to spend time with — maybe even befriend at least one such person.

This experience was powerful because when I decided to listen, and not to judge, I began to understand how fragile life can be — how close all of us are to being on the fringes of survival.

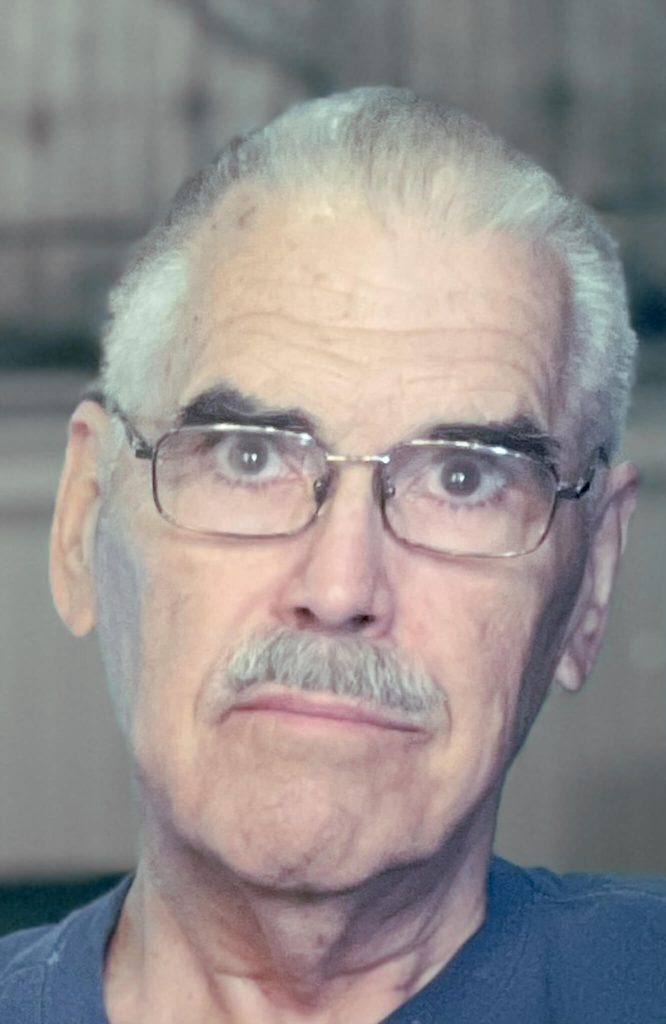

I spent one long day with 69-year-old Eddie Cortez, who had been sleeping behind one of the buildings on the west side of D Street in Perris. He appeared to have awakened sleepy and grumpy — not just today, but for several years. And he was eager to talk about himself.

He told me that he had an amazing story to share.

“I never knew my mother at all,” he said as we sat on a bench outside the Perris Market. “My father sent me to live with my grandparents. I never knew why he didn’t want me.”

It was only after he had completed school that he learned from one of his so-called uncles that his father had lied to him.

“My uncle told me that my grandparents weren’t my real grandparents,” he said. “They were friends of my father. So, all of a sudden, I realized that all that time, I didn’t belong.”

I didn’t tell him how I had experienced a similar feeling when I was seven. My father had broken the news to my sister and me that he wasn’t our father. We never spoke about what he had told us. We both thought that he might have been lying. He had died two years after our mother divorced him. It would be nearly 40 years later that a DNA test proved that he had been telling the truth.

I also felt as if I hadn’t belonged.

Eddie told me that after high school he had worked for a while in various jobs but somehow, he ended up on the street. Apparently, he didn’t feel comfortable talking about his downward spiral or when he hit the skids.

“I’m all alone,” he said as I walked with him to a secret place where he keeps his things and occasionally crashes. It’s in an abandoned outbuilding. He surprised me when I asked him what, if anything, he’s thankful for.

“The sheriffs,” he said. “I’m thankful for the sheriffs because they leave us alone and don’t bother us. They look out for us. They tell us to be careful because it can be dangerous on the streets.”

There’s one deputy who is even more caring than the rest, he said. He told me her last name, but the Sheriff’s didn’t respond to my requests for confirmation.

Eddie wasn’t the first person to give praise to local law enforcement.

I had met 35-year-old Nathan Russell sitting on the sidewalk against the outside wall of a retail drug store not far from the Menifee Post Office in Sun City. I introduced myself as a journalist, we chatted for a few minutes, and he invited me to sit down with him.

“I’ve been hoping to talk to a reporter,” he said. “I have a big story to tell you about.”

His skateboard and his weathered backpack were the only visible clues that he was living on the streets. Otherwise, he was well-groomed and was dressed in clean, casual attire. He spoke like a professional.

Even though Menifee police officers arrested him once, he said, they don’t bother him anymore.

“They were checking me out because the sheriffs told them I was a terrorist. Now they’re helping me out. Now they’re leaving me alone.”

That would be the beginning of an hour-long description of how the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had ruined his life — and were watching him every minute of the day.

“The United States Army Corps of Engineers is like the jack of all trades,” Nathan said. “They subcontract for the Sheriff Special Forces. They do their own programs. They subcontract for the Department of Homeland Security. They subcontract for the Department of Disability and Aging they’d subcontract for the Health and Human Services.”

Long story short, Nathan says that he fathered a child with a woman who was somehow connected with the Corps of Engineers — the agency that, today, controls every aspect of his life.

They are responsible, he says, for the courts preventing him from ever seeing his son.

I should make it clear that each person with whom I spoke understood that I wasn’t there to question, judge them or doubt what they were saying.

Regardless of the circumstances, my heart was with him.

I didn’t tell him that I, myself, had only recently learned that I had fathered a boy who was born in 1972. Oh, how I regret that I hadn’t been able to know him when he needed a father.

Next, I went to Perris to do a follow-up interview with Denise Bustamante, the woman I had written about two weeks ago when American Legion Post 595’s Chaplain Ed Moreno encountered her on D Street with all her possessions. She was more than happy to tell me about the things that he had provided her — a sleeping bag, clothing, shoes, personal items and more.

She looked radiant —so much healthier and happier than the day I first encountered her.

First and foremost, she said she’s grateful for being close to God — and grateful that Jesus will soon return.

“I’m thankful for just God always being there for us, getting us through the hard times, getting us through everything. Without him, you know, we wouldn’t have breath without him.”

She also suffered when her parents sent her to a foster home when she was very young. The second time I spoke with her she said she now believes that her birth parents had been sent to prison. It was the only scenario she could imagine — why else would they give her away?

She said that she believes that God put her on this earth to protect people.

Denise’s dream, she said, is somehow reuniting with the son she has not seen in more than a decade.

Doug Daniels traces his earliest trauma to when he was a child. He described how his successful and wealthy father — a renowned physician — had been harsh and over-demanding of him, and that his mother kept him undernourished and kept him “caged up” all day in a crib.

“My first memory was of a mother who didn’t, couldn’t bond with me,” he said. “There was no love. Yeah, so she basically kept me alive in a little jail.”

When his younger sister came along, he recalls, it seemed as if she got all the attention. He said he felt worthless.

Again, I bit my tongue. I thought about how alone I felt as a child — how the man we thought was our father adored my older sister. At the same time, he would beat me with such anger that it was clear that he despised me.

Doug said he dutifully went to college, but knew that he neither wanted to be, nor was he capable of following in his father’s footsteps. He would not become a physician one day. In fact, he said, he ended up traveling across the U.S. working at outdoor, seasonal, jobs.

He told me that he has been “camping” ever since.

“But yet I always felt like I let my parents down by not having a career. And they let me know they weren’t pleased.”

As I sat down to write this Thanksgiving story, I thought about how I had experienced so many things these four people had endured.

I had suffered from child abuse. I had felt unworthy of being loved. I would learn on the day I came home from Vietnam that my sometimes-abusive stepfather had been in prison for many years for armed robbery and for stealing thousands of dollars from a bank. I would know the pain of missing out on knowing my own son.

The experience made me realize that, despite dodging many of life’s obstacles, I am so very lucky.

Now, for the first time, I’m beginning to understand what my first counselor at the Veterans Administration meant 25 years ago when he said to me, “The more I learn about your childhood, the more amazed I am that you didn’t end up in jail or on the streets.”

This Thanksgiving, I am more thankful than ever.

A proud Vietnam Veteran, Don Ray is also a six-decade veteran multimedia reporter, writer, editor and producer for scores of print and visual media outlets. He as reported from Guatemala, Nicaragua, Mexico, the Philippines, Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, and trained journalists in emerging nations across Africa and Europe. You can reach him at donray@donray.com.

For More Ray of Light Articles Visit www.zapinin.com/ray-of-light.