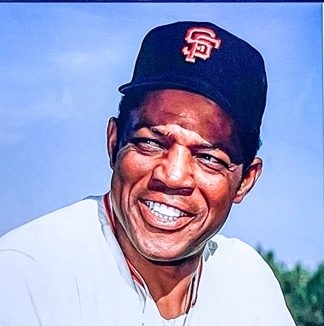

Willie Mays – A Personal Reflection

BY JIM FORBES, PUBLISHER

From the time I was 5 years old, he inspired my lifelong love and passion for baseball. He played it with the exuberance of a kid while becoming the greatest ever! He was infectious to watch.

Ailey, Joyce, Picasso, Leontyne Price on a diamond.

“The Say Hey Kid,” #24, Willie Mays the icon who played stickball for fun, and for free, with the neighborhood kids outside the Polo Grounds AFTER giving his all for 9, sometimes 18, innings inside the Harlem stadium where he was paid to play, touched home plate Tuesday afternoon at the age of 93.

He passed only two days shy of last night’s celebration at his childhood home park, the 114-year-old Rickwood Field in Birmingham, AL. That was where he played as a 16-year-old high schooler, with professionals, grown men, including his dad, for the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro Baseball League. It was 1948, the year after Jackie Robinson began the integration of the all-white Major League Baseball.

With the color barrier broken, the Giants drafted Mays in 1950 when he graduated high school. He was called up to the major leagues in early ʻ51, starting his big league career, 0 for 12. That is, no hits in 12 at-bats. The disconsolate Mays was ready to go back to the minor leagues, but his colorful manager, Leo “The Lip” Durocher would hear none of it, instilling confidence in the youngster.

On May 28, 1951, 22 days after his 20th birthday, he dug in at the plate in the first inning, facing one of the most dominant pitchers of the era, future Hall of Famer, Warren Spahn. Mays promptly deposited a Spahn offering over the left field roof and he went on to be named the National League Rookie-of-the-Year.

From early 1952 and through 1953, Mays served in the Army. Leaving baseball after one year and just 34 games in his second season before joining Uncle Samʻs military, he had alr4eady established a deep respect from teammates and opponents alike.

Veteran San Francisco sportswriter and Mays biographer John Shea, recalled in a broadcast interview on Wednesday, that after his last at-bat in the Brooklyn Dodgers Ebbets Field before heading off to boot camp in ʻ52, the archrival Dodger fans gave him a send-off with a standing ovation.

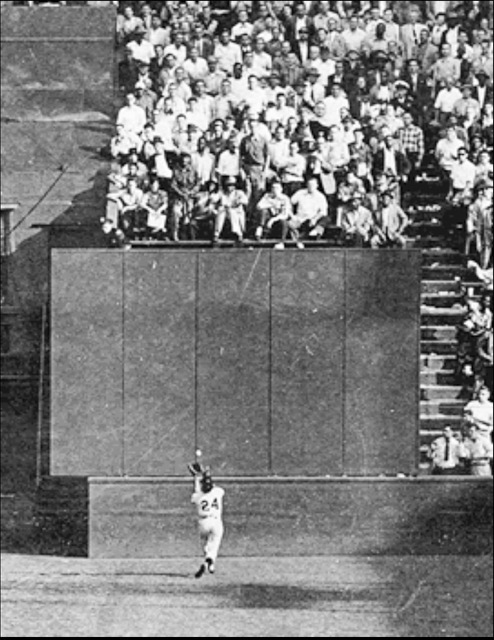

When he returned to the league for the 1954 season, he led the Giants to a World Series sweep of the heavily favored then-Cleveland Indians. Mays was league MVP and made a legendary over-the-shoulder catch in Game 1 in the cavernous centerfield. He always professed to be just as proud of the ensuing throw, preventing a runner from scoring, as the play that is simply known in baseball lore as, “The Catch.”

Beloved in New York, San Francisco fans were slow to adopt Mays as fully when the team joined the Dodgers in moving west in 1958, throwing a bit more love toward San Francisco debuting rookies Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda.

But the infectious, hustling, kid-like Mays was the leader-of-the-pack by 1962, when the Giants beat the Dodgers in a 3-game playoff for the pennant before losing to their old neighbors across the Harlem River, the Yankees in a seven-game World Series.

Among the many greats of the era, Mays stood out for the depth and breadth of skill unlike, any other. And that infectious personality.

Mays biographer Shea, remembered a conversation with Dodgers great, shortstop Maury Wills about the level of respect the Dodgers had for their most prolific opponent.

Wills referenced the brutal 1965 incident when Giants pitcher Juan Marichal was batting, and he believed Dodgers catcher John Roseboro purposely whizzed a ball by Marichalʻs head in a return throw to the pitcher. Marichal turned around and began hitting Roseboro in the head with his bat, one of the ugliest incidents in baseball history.

In Wills recollection of the mayhem to Shea, in the ensuing brawl, Mays saw how badly injured the bleeding Roseboro was, and he ushered the badly wounded player from the pack and brought him to the Dodgers bench.

Wills told Shea that Mays was the only opponent his teammates respected so deeply, that they allowed that to occur.

After Maysʻ peer, the great Roberto Clemente was killed in a 1972 plane crash while providing aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua, Major League Baseball created an award in Clementeʻs name, honoring the player “who best represents the game of baseball through extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.”

Willie was the first winner.

“Iʻd rather always be good than sometimes great,” former players recall him saying. “Practice like a pro, play like a kid.” Did he ever!

From the creation of the NY Mets in 1962 through 1972, there wasn’t a year I missed the Giantsʻ four visits to NY. And then even more games, in ʻ73, when he finished his career in the city where it all started.

As a former baseball writer and Hall of Fame voter, my dad let me fill in the circle voting for Willieʻs first ballot entry into the Hall.

Twenty-two-time all-star, 24 years my senior, in ʻ24 #24 takes his legacy north from the spring training of life.

Heaven is about to be far more exciting. Not so much, here. Skip across the clouds with that youthful joy, your unique generational athleticism, and your innate enthusiasm, no longer constrained by mortal age.

Thank you Mr. Mays for all the joyful memories! And for the Giant, inspirational man, you will always be.

For More Sports News Visit www.zapinin.com/sports.