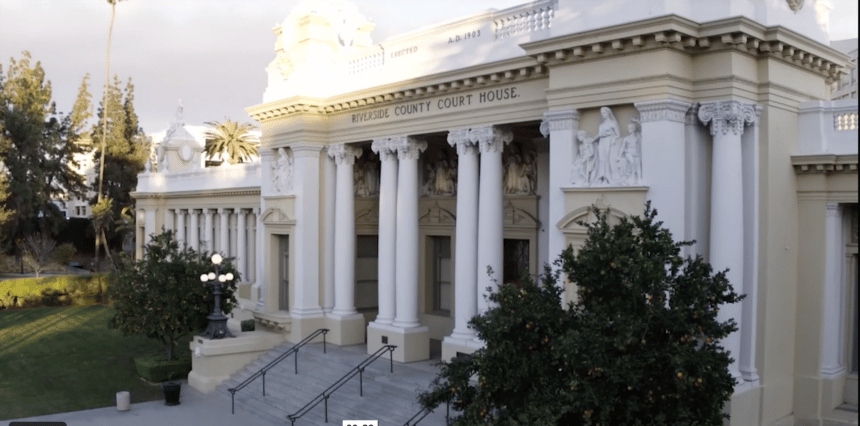

RIVERSIDE (CNS) – The first appellate action to challenge a wave of dismissals by Riverside County Superior Court judges trying to slice through a backlog that accumulated during the COVID lockdowns is underway, the county’s top prosecutor announced Monday.

District Attorney Mike Hestrin said the agency wants the case of People v. Jose Luis Tapia returned to the docket for trial. It involves a machete assault that occurred in the Blythe area.

Prosecutors filed an emergency writ at the end of last week, notifying the Fourth District Court of Appeal in Riverside that they are challenging the trial court’s decision to boot the matter and are prepared to argue the merits of continuing proceedings, rather than permit the defendant to walk away without answering the charges.

Tapia’s is one of an estimated 350 criminal cases dismissed since Oct. 10 by judges countywide, citing lack of available judicial resources — or courtroom space — to receive a speedy disposition by trial, as guaranteed under the state constitution.

The matter is one of roughly 2,800 cases that piled onto county courts’ dockets going back to when the Office of the Chief Justice of California changed courts’ operations statewide in 2020, permitting ongoing postponements, amid the lockdowns.

However, all of the chief justice’s emergency orders expired on Oct. 7.

“Unless the courts stop these dismissals, the backlog of criminal cases will grow, and our justice system will be in danger of collapse,” Hestrin said in a video message released last week.

The majority of cases dismissed to date have been domestic violence matters.

“When a judge dismisses a domestic violence case, they also terminate the victim’s criminal protective order. This is nothing less than an injustice and a disservice to the victims and to public safety,” Hestrin said.

Superior Court Presiding Judge John Monterosso released a statement Tuesday acknowledging the court system was bearing a heavy load, traced to the lockdowns and consequent changes in court operations.

“I share others’ frustration when a case is not resolved on the merits, or due process is impaired, due to a lack of available judicial resources,” Monterosso said. “The genesis of the current set of circumstances is the chronic and generational lack of judges allocated to serve Riverside County.”

He emphasized that the county has 90 authorized and funded judicial positions, but a 2020 Judicial Needs Assessment Study noted that 115 judicial officers are needed to ensure efficient operations throughout the local court system and prevent logjams.

“The dispensing of statutory timelines for criminal trials under the emergency orders delayed the `day in court’ for numerous criminal defendants and those impacted by the alleged crimes,” Monterosso said. “While the law allows a court to continue a case beyond the statutory deadline for `good cause,’ the decision on whether `good cause’ exists is an individualized decision made by the trial judge based on the law and the facts of the case.”

Hestrin sympathized with the fact “we have far fewer … judicial seats than we need based on population.”

“But this has been the case as far back as anyone can remember,” he said. “Before the pandemic, we had not had a criminal case dismissed for lack of a courtroom in over a decade.”

He said defendants whose cases have been repeatedly delayed are watching the current drama unfold and “have no incentive to resolve any matter before trial” as long as there’s a possibility that holding out will ultimately lead to a dismissal.

“This situation is unsustainable and constitutes a danger to the public,” Hestrin said. “We’re not asking for a specific outcome. We’re asking judges to engage with the facts of the cases and backlog.”

Monterosso countered that judges are redoubling efforts to accommodate trial requests, often times summoning prospective jurors for screening late on weekdays to courtrooms where juries in other matters are still deliberating.

However, Hestrin said earlier this month, 500 prospective jurors slated to be assigned courtrooms were sent home, with judges refusing to entertain requests for “brief” postponements until courtrooms became available.

“(This) seems like mismanagement of resources,” the D.A. said. “If we have an emergency in our courts that justifies a dismissal of a felony, then it should be an emergency in every courtroom across the county and should justify an all-hands-on-deck approach to trying cases.”

He recommended longer hours each weekday, the start-up of night courts and even weekend court hours to plow through the backlog. It was unknown what costs in overtime and other budget pressures those actions might precipitate.

The current backlog is reminiscent of the cumulative impact of a buildup of unresolved criminal cases in 2007 that prompted the state to dispatch a judicial strike team to the county to help sort through criminal cases clogging the court system.

At the time, the Superior Court virtually halted civil jury trials for months while judges focused on reducing the strain on resources. An empty elementary school was even converted into a makeshift courthouse.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.